Update time:2026-02-07Visits:537

Dr. Cui Song

Profile

Doctor Cui Song holds a Master of Medicine and serves as Chief Physician in the Geriatrics Department of Shuguang Hospital, affiliated with Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). He is an Associate Professor and Master’s Supervisor. His professional roles include membership in the Cardiovascular Disease Branch of the Chinese Association of Traditional Chinese Medicine, standing committee membership in the Heart Disease Branch of the Shanghai Association of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and recognition as a Leading Talent in TCM for Shanghai. He is also a National Academic Inheritor of Senior TCM Experts and Deputy Director of the Psychosomatic Medicine Subspecialty Branch of the Shanghai Medical Association.

Areas of Expertise

Professor Cui specializes in an integrated Traditional Chinese and Western medicine approach to diagnosing and treating arrhythmia, heart failure, hypertension, and post-operative care for coronary heart disease. He is particularly focused on managing the "dual-heart" connection—the interplay between cardiac and psychological health—by combining TCM, Western medicine, and psychological principles.

A Commitment to Public Health

Since 1999, Dr. Cui Song has been dedicated to public science communication, demystifying Traditional Chinese Medicine for a broad audience. With extensive experience, a solid foundational knowledge, and a gift for clear explanation, he has become a leading voice for TCM popularization in Shanghai. He is guided by a simple philosophy: to disseminate accurate medical knowledge, steer the public away from health misinformation, and improve overall health literacy.

His advisory roles are numerous, including: expert for the National Administration of TCM’s Culture and Science Lecture Tour; member of the Science Popularization Branch of the Chinese Medical Doctor Association; founding expert of the National Health Science Popularization Expert Database; and lead TCM expert for Shanghai’s Public Health Literacy Enhancement Project. He enjoys a strong public reputation and considerable social influence.

In His Own Words

"Choosing a career in medicine may happen by chance, but once chosen, it demands a lifetime of devotion and passion." — Inspired by Dr. Zhong Nanshan.

The reasons for choosing a career in medicine are as varied as the individuals who pursue it. Some are called by the times they live in, some by family expectations, and others by a sense of destiny. Yet, this initial choice is merely the first light of dawn on a healer’s journey—the prelude to a lifetime of honing their art.

The subject of our story is no exception. For him, medicine was both a family expectation and a fateful calling. From his first steps out of medical school into clinical practice, he navigated the gap between theory and reality, embracing the continual cycle of learning—reviewing the old to understand the new. Day after day, case after case, he began to document, from a healer’s perspective, the insights and regrets inherent to the human condition. This practice became the driving force behind his dedication, since 2010, to communicating science to the public.

By now, you may have guessed: this is Professor Cui Song. He ranks 4th on the 2023 Healthcare Professionals’ Health Science Communication Influence Index and serves as Chief Physician of the Geriatrics Department at Shuguang Hospital, affiliated with Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

“In my view,” he reflects, “the place where you hear the most prayers is not a church, but the walls of a hospital. Here, you consistently encounter the most moving, most genuine, and most heart-wrenching scenes.” Patient suffering, he observes, is not merely physical; it often stems from the depths of the heart. Thus, healthcare transcends treating disease—it becomes an exchange between hearts, requiring genuine compassion to soothe inner wounds. He is committed to a threefold approach, integrating Chinese medicine, Western medicine, and psychology to treat what he calls the “dual heart”—the interconnected ailments of body and mind.

1. The Path to Medicine

Step into Shanghai’s Old Nanshi district, and you feel transported to another time. Here, towering buildings are scarce; instead, a compact tapestry of life unfolds along winding alleyways. The slightly mottled walls of Shikumen houses, with their blue bricks, dark tiles, and wooden frames, hold a historical charm more authentic than the polished façades of Xintiandi. With every breath, you sense the unique cultural atmosphere of old Shanghai. Slanting afternoon light brushes faded wall corners, and dappled shadows dance with the passing of pedestrians—a quiet interplay of history and modernity.

“When people speak of Shanghai’s origins, they often mention Songjiang,” Cui Song notes. “But the Old Ximen area in Huangpu District is also a vital source—the historical root of today’s Shanghai. Since Shanghai County was established in 1291, this has been the seat of its government. It is also my home.” Unexpectedly, the professor well-versed in medical communication also possesses deep insight into the history and architecture of the old city.

Over a pot of freshly brewed tea, our interview begins in the hazy light of the old city afternoon.

“My family is a typical ‘educated youth’ household. In her youth, my mother answered the national call and left Shanghai to support development in the border regions. That was in 1968—she was in the bloom of her youth. Fate, however, is unpredictable. She had expected to settle there for life, until a new policy was announced: one child per family could return to Shanghai at age sixteen. Again, the age of sixteen—but this time, it meant a return, not a departure. A choice had to be made. With two children, my parents could send only one back. After much reflection, my father transferred to work in Wuxi, bringing us closer to Shanghai. It was a decision made entirely for their children’s future—a testament, like so many parents’, to their profound care and sacrifice.”

In 1990, Cui Song was a high school student facing a pivotal choice. At the time, science and engineering degrees were all the rage, encapsulated by the popular saying, “A good grasp of maths, physics, and chemistry opens every door.” Yet his father, a university professor, urged a longer view. He advised Cui Song to look beyond fleeting trends and consider medicine.

Cui Song rose to the challenge, earning outstanding marks and a place at the nation’s premier institution for traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)—Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Founded in 1956, the university was among the first four TCM institutions established in New China. It was formed by merging several prestigious Republican-era schools, including the Shanghai Specialized School of Traditional Chinese Medicine (founded 1917), the Shanghai Chinese Medical College (1927), and the Shanghai New China Medical College (1935). From the outset, it held a distinguished position in Chinese medical education.

To this day, Cui Song recalls the atmosphere on campus: the walls adorned with calligraphic masterpieces and famous quotations, each exuding a profound scholarly heritage and centuries of TCM wisdom. Here, Eastern and Western medicine converged. Lecturers in white robes would expound on classical texts and practical experience, while professors of Western medicine taught their own rigorous curricula. History and tradition permeated every corner, and through a demanding educational system, the university produced generation after generation of capable, conscientious practitioners.

After graduating in 1995, Cui Song began his residency in the cardiology department of Shanghai Shuguang Hospital. This was his new stage. He quickly realised that textbook knowledge alone felt insufficient in the face of real clinical challenges. What he first saw as the “shortcomings” of modern medicine soon became a driving force for deeper learning.

A valuable opportunity arose when he was selected for further training in the cardiology department of Shanghai Zhongshan Hospital. There, he observed and assisted in cardiac interventional procedures under the guidance of Academician Ge Junbo. This experience opened a new professional world and underscored the irreplaceable value of hands-on clinical practice.

Upon returning to Shuguang Hospital, Cui Song developed a habit of meticulously documenting each surgery—not only the diagnosis and treatment, but also his own reflections. Over time, he noticed that some patients’ symptoms involved not just organic issues, but psychological complications arising from their illness. As his experience grew, he recognised that conditions like anxiety, depression, and panic were frequent, overlooked factors in a patient’s discomfort. He became convinced that a deeper understanding of this intersection between physical and mental health was essential to modern care—and he was determined to find solutions.

In 2005, Cui Song sought a new professional challenge. He enrolled in the Sino-German senior psychotherapist training programme at the Shanghai Mental Health Center. There, he studied diverse psychotherapeutic methods, gradually mastering the interpretation and application of psychological principles in treating disease. This advanced training equipped him with a multi-dimensional medical perspective, aligning with a global shift in healthcare philosophy—from a purely biomedical model toward a holistic approach that emphasises the patient’s psychological state and overall wellbeing.

Despite his extensive training, Cui Song felt his knowledge was never complete. This “learning anxiety” became a constant driver, preventing any sense of complacency. In 2008, a new chapter opened when he was selected for the National Programme for Inheriting the Academic Experience of Veteran Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioners. He had the privilege of studying directly under the renowned TCM professor He Liren. Through this mentorship, Cui Song’s understanding of Chinese medicine deepened, and he began to explore how to integrate TCM with modern medical practice.

In 2018, Cui Song was named a Leading Talent in Shanghai’s TCM field. Despite the honour, he remained humble and diligent, never satisfied with the status quo. He understood that medicine is a field of endless learning, and that only through continuous study could he better serve his patients.

2. Integrating Chinese and Western Medicine, Uniting Doctor and Patient

Life is both fragile and resilient; the partnership between doctor and patient makes this resilience powerful. In Cui Song’s view, every patient represents a story worthy of respect and full dedication. It is this philosophy that has fostered remarkable collaboration, turning each battle against illness into a purposeful journey toward healing.

Cui Song firmly believes that a doctor’s mission is to continually advance medical knowledge while using both clinical skill and humanistic care to nurture each patient’s life.

In treating heart failure, he has developed an integrated Chinese-Western approach. Upon admission, the conventional Western protocol typically addresses symptoms by inhibiting ventricular remodelling, administering diuretics and vasodilators, correcting electrolyte imbalances, and providing anti-infection therapy. In the early stage, careful diuresis is crucial for managing heart failure. As treatment progresses, Traditional Chinese Medicine is employed to address the root cause—fortifying the body’s vitality, warming yang, promoting blood circulation, and nourishing yin. While Western medicine focuses on controlling the disease, Chinese medicine aims to strengthen the patient’s own resistance. Supporting the body while managing the illness is woven throughout the entire treatment process, achieving strong clinical results.

Beyond physical treatment, Cui Song places great importance on the role of mental wellbeing in recovery. He recognises the psychological toll of illness and, alongside medication, emphasises psychological comfort and support for his patients. Here, he finds Traditional Chinese Medicine offers unique advantages. Through attentive communication during consultations, it can provide psychological solace and emotional release, helping to alleviate the patient’s suffering.

Cui Song is convinced that the evolution of modern TCM requires continued innovation and clinical practice. He stresses that medical skill should not be measured by patient volume, but by patient recovery. Only when a patient is truly healed, he believes, can a doctor’s expertise be fully affirmed.

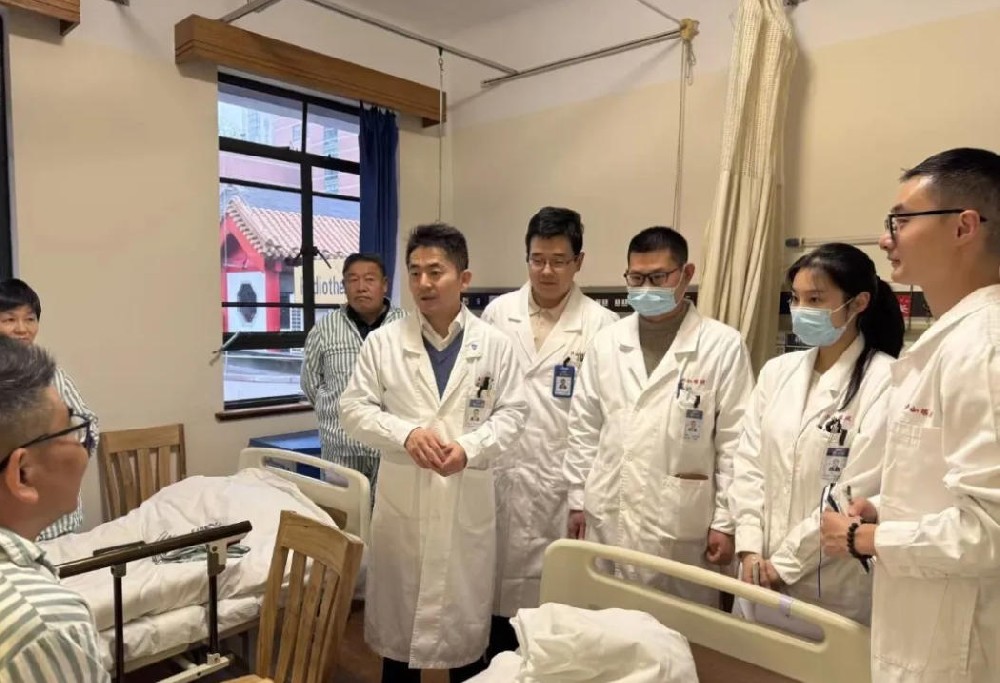

In the spring of 2007, a single patient left an indelible mark on Dr. Cui Song.

In the ward lay a young girl, her face pale, the steady beep… beep… beep of the monitors the only sound at her bedside.

Fulminant myocarditis had brought her to the brink of death. At that critical moment, an ECMO machine had served as her lifeline—until she was transferred to the care of Dr. Cui and his team.

He still remembers their first meeting.

"Despite suffering from severe heart and lung failure, her spirit was remarkably tenacious. She was a tall girl, and her considerable weight made every breath a visible struggle. Yet, her eyes held a firm resolve, a fierce will to live. I was profoundly moved. It steeled my own determination to do everything possible to save her."

After a comprehensive assessment, Dr. Cui decided on an integrated treatment strategy, blending Western and Traditional Chinese Medicine. He believed that for such a complex case, a conventional, single-approach treatment would be inadequate.

"The test results were stark. Her heart was severely enlarged, the muscle wall dangerously thin. Her ejection fraction was only 18%. I recall explaining to her father that in such a state, the greatest risk was sudden cardiac arrest."

The initial evaluation suggested that practically every applicable medication had already been tried. At best, they could consider implanting a cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). But an ICD is merely a safety net; it does not treat the underlying condition. As heart failure progressed, it could trigger dangerous arrhythmias and further complications. The urgent priority was to discover why the medications were failing, in hopes of arresting the heart failure’s progression.

The girl’s father told Dr. Cui, "I know my daughter’s condition is grave. She has already lost her mother, and I lack the means to support her long-term. But if I can just afford her treatment, and if we can have some good days together, that will be enough." His words were tinged with sorrow and resignation, yet carried a quiet, philosophical acceptance.

Dr. Cui was deeply moved by the man’s strength and selflessness. "I will do everything in my power for your daughter," he assured him, his voice firm.

Drawing on his full knowledge of both medical traditions, Dr. Cui crafted a personalised treatment plan for the young patient.

The path ahead was arduous, a test not only of medical skill but of the resilience of doctor and patient alike.

"I began to question why the standard treatment had failed. Then I considered her weight. Two issues became clear: first, if she was over 100 kilograms, that mass alone placed a constant strain on her failing heart. Second, excessive weight often means drug dosages calculated by body surface area are insufficient. I advised the team to re-evaluate both her metrics and her prescriptions to optimise their effect."

Dr. Cui Song began to consider whether the treatment strategy needed adjustment, and whether the medication dosage should be modified according to her weight and physiological condition. This tailored approach, he believed, might more effectively restore her heart function and prevent further deterioration.

He decided to adopt a gradual method, incrementally increasing the dosage until it reached twice the standard level.

The treatment began with wild ginseng powder as the initial phase of herbal therapy. This was followed in the mid-phase by custom decoctions, later switching to prepared herbal formulas. Gradually, as the girl’s symptoms eased and her mood stabilised, a smile returned to her face.

“I was truly pleased, because her reduced need for frequent consultations was a clear sign of improvement. However, there was a setback during her recovery. Her aunt, thinking she was doing well, encouraged her to find some light work. But after just a few days, she experienced shortness of breath and required hospitalisation again. Fortunately, her recovery this time was swift.”

3. A Guide to Medical Outreach

One of Cui Song’s most memorable experiences was a medical volunteer trip to Xinjiang in the winter of 2018, where he delivered health education lessons to local secondary school students.

“I contacted the Regional Health Commission in advance to understand local health knowledge gaps and common diseases. We flew over five thousand kilometres to reach Kuoshitage Township in Pishan County. Standing before the children, I saw a genuine thirst for knowledge in their bright eyes. To engage them, I prepared animations and visuals. When teaching handwashing, I even brought a germ-detection device for a live demonstration. I hoped the lesson would inspire them to wash their hands properly—and gave them soap and towels as gifts, which delighted them.”

After a second session on preventing iodine deficiency, the children gathered around Dr. Cui, asking to take photos together. In his view, children are the nation’s future, and health awareness must be nurtured from an early age—that was the deeper meaning of the Xinjiang trip. The success of this outreach reinforced his conviction that public health education is a vital service to society, one worth sustaining.

Cui Song’s journey in health communication began in 1999, when he was invited by Shanghai Cable Television to host the programme Towards Health. From 2000 to 2007, while hosting medical education programmes at Shanghai Education Television, his passion for the work grew. He engaged extensively with medical experts, broadening his own knowledge and expertise.

Through this process, he refined his communication skills, laying a foundation for his long-term commitment to public health. In 2010, Cui Song was appointed among the first group of National Experts in Traditional Chinese Medicine Culture and Health Communication. He began appearing as a guest on Shanghai Television, successfully transitioning from programme host to recognised health education specialist.

Now in his forties, and with years of practical experience behind him, Cui Song has dedicated increasing energy and time to public health education. In 2014, at the invitation of the Shanghai Health Education Institute, he recorded his first science communication video, producing a programme called Medical Knowledge Stands Out in a novel "talk show" format. Over the following years, he completed more than one hundred episodes, consolidating and disseminating prevention and treatment knowledge for over 100 diseases.

Cui Song soon expanded his efforts online, opening an account in 2015 to share audio clips from Medical Knowledge Stands Out. By providing clear answers to the public’s health questions, he earned widespread praise. In 2018, he published his first popular science book, offering an accessible resource for audiences with different reading preferences.

When the COVID-19 pandemic swept the globe in 2020, Cui Song, as an experienced science communicator, stepped forward during the crisis. He participated in 15 Shanghai press conferences on pandemic prevention and control, helping to clarify public concerns and boost confidence. He also leveraged short-video platforms to disseminate scientific guidance, raising public awareness of effective epidemic prevention measures.

Today, Cui Song is a leading figure in health communication. He remains committed to his original mission: spreading practical health knowledge to improve the nation’s health literacy. While grateful for the honours he has received, he approaches them with humility. For him, the work of public education remains a long and demanding journey—one that requires continued dedication to the cause of national health.

/ Interview /

ShanghaiDoctor.cn: You were recently named an "Outstanding Figure in Shanghai Public Science Communication" and ranked 4th on this year’s list of the Top 100 Most Influential Professionals in Health Communication. What do you attribute these achievements to?

Cui Song: After nearly 30 years in medicine, I have long considered science communication a "long-term prescription" for preventive care. Explaining medical knowledge clearly, whenever and wherever I can, has become almost a professional reflex. In everything I do, I try to remember that I’m addressing not just one patient, but a whole community. That awareness always stays with me. Of course, it starts with medical expertise—that’s the foundation. Everything else is just a tool to make that knowledge more accessible and engaging for people.

ShanghaiDoctor.cn: After all these years in science communication, what has been your most memorable experience?

Cui Song: An unforgettable "handwashing masterclass." It profoundly shaped my approach to public communication. This was in 2018, shortly after I won first prize in the National Science Popularisation Explanation Competition. I took part in the National Health Commission’s "Famous Doctors to the Grassroots" poverty-alleviation tour in Xinjiang, where I led a science session in a middle school classroom in a remote ethnic minority region.

This was my first science outreach presentation, titled “The Blooming Hand.” I began by showing the students an image and asking, “What is this?” They would, of course, say it was a hand—but why would a hand “bloom”? This curious question immediately captured their attention. I then explained that before coming to the class, I had pressed my unwashed hand onto a laboratory petri dish. So what exactly was the “dirt” on my hand? The children watched with wide, curious eyes, eager to explore the unknown. I told them, “It’s Staphylococcus! And here in Xinjiang, everyone knows what grapes look like!” Sure enough, by using relatable, everyday examples, the students grew excited and began answering eagerly. The first outreach class had successfully broken the ice.

As the session drew to a close, I had the students use the ATP detector I brought to test the bacteria on their own hands. They observed and compared the readings before and after washing their hands right then and there. Transforming the abstract idea of germs into a hands-on experiment allowed the students to personally grasp the presence of bacteria and the importance of hand hygiene. This approach not only improved learning outcomes but also sparked their interest in science and gave them a deeper understanding of health. By combining education with engagement, this method helps foster scientific literacy and health awareness in students. Without a doubt, it was an unforgettable experience for the children in Xinjiang.

ShanghaiDoctor.cn: What, in your view, is the essence of integrating traditional Chinese and Western medicine?

Cui Song: This is a question that TCM experts have long explored. I wouldn’t presume to give a definitive answer, but I can offer my perspective. First, the integration of Chinese and Western medicine is an inevitable trend.

However, integration doesn’t mean simply adding one to the other. Rather, it means combining the strengths of both systems according to the needs of the patient. In practice, we must be clear: when should TCM take the lead, and when should it play a supporting role? In treatments led by Western medicine, when is it most beneficial to introduce TCM? Our shared goal is for the two approaches to complement each other and improve efficacy.

Second, we need a degree of alignment between the diagnostic frameworks of the two systems. For instance, we should avoid a situation where one side speaks of “coronary heart disease” while the other discusses “chest impediment,” or one mentions “heart failure” while the other refers to “edema.” Only by speaking a common language can we communicate effectively, combine our strengths, and achieve true synergy. This is also a goal every TCM practitioner should strive toward: developing a new diagnostic framework that maximizes patient benefit.

Third, in the age of AI, TCM must embrace knowledge from other disciplines to promote its preservation, innovation, and development. Clinging to old ways is no longer feasible.

For example, with coronary heart disease patients, TCM shouldn’t rely solely on promoting blood circulation and removing stasis. For febrile patients, it shouldn’t default to clearing heat and detoxifying. We must learn to apply TCM thinking dialectically, tailoring treatments to the individual.

ShanghaiDoctor.cn: We know that LDL cholesterol is closely linked to atherosclerosis. Excessively high levels can lead to a range of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. But should this indicator also be approached with a uniform standard?

Cui Song: No. The “healthy” range for LDL cholesterol differs across populations.

First, for individuals at low risk—meaning the general population with no major risk factors—the target level for low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol is 3.4 mmol/L. As long as readings remain at or below this level, they are considered within the normal range.

For those at moderate to high risk—including people with hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease (stages 3–4), long-term smokers, or individuals with obesity (BMI ≥28)—LDL cholesterol should be maintained below 2.6 mmol/L.

In very high-risk cases, such as patients diagnosed with atherosclerosis, LDL cholesterol must be controlled below 1.8 mmol/L, with an ideal reduction of at least 50% from baseline.

In 2023, China’s Guidelines for Lipid Management introduced a new classification: ultra-high-risk individuals. This category includes patients who have experienced two or more major cardiovascular events—such as myocardial infarctions or cerebral infarctions—or those who have undergone surgery for peripheral vascular disease. For this group, LDL cholesterol should be kept below 1.4 mmol/L, again with an optimal reduction of 50%.

ShanghaiDoctor.cn: What are your interests outside of work?

Cui Song: I have a broad curiosity about the world and quite wide-ranging interests. I’d be happy to discuss architecture or history, for example. I also enjoy photography and take real pleasure in capturing beautiful moments in everyday life. When I travel, I often use my camera to record landscapes, people’s expressions, or the mannerisms of animals. Through elements like light, composition, and colour, I try to convey reflections on themes such as life and nature.

Dr. Bao Shihua | Where Dreams Begin from Reproductive Immunology

Dr. Yang Zhigang | The Art of the Healer: Between the Brush and the Brain

Dr. Cai Junfeng | Guarding Bone and Joint Health, Improving Quality of Life

Dr. Xu Xiaosheng|The Gentle Resilience of a Male Gynecologist

Dr. Shi Hongyu | A Cardiologist with Precision and Compassion

Dr. Zhang Guiyun|The Inspiring Path of a Lifesaving Physician

Dr. Cui Song | Healing the Heart, in Every Sense

Dr. Bao Shihua | Where Dreams Begin from Reproductive Immunology

Dr. Yang Zhigang | The Art of the Healer: Between the Brush and the Brain

Dr. Zhou Qianjun | Sculpting Life in the Chest

Dr. Cai Junfeng | Guarding Bone and Joint Health, Improving Quality of Life

Dr. Cui Xingang | The Medical Dream of a Shanghai Urologist

Dr. Xu Xiaosheng|The Gentle Resilience of a Male Gynecologist

Dr. Shi Hongyu | A Cardiologist with Precision and Compassion

Dr. Zhang Guiyun|The Inspiring Path of a Lifesaving Physician

Dr. Jiang Hong | Bringing Hope to Vascular Frontiers